He is calculating and devious. He is interested only in power and takes any opportunity to take advantage of situations will advance his ambitions. He is behind the murder of King Hamlet, but Prince Hamlet lacks concrete proof of this fact. Hamlet’s mother and the Queen of Denmark. According to Eliot, the feelings of Hamlet are not sufficiently supported by the story and the other characters surrounding him. The objective correlative's purpose is to express the character's emotions by showing rather than describing feelings as discussed earlier by Plato and referred to by Peter Barry in his book Beginning Theory: An. A character's objective will vary according to: a. The character's consciousness of his wants. Hamlet's energy may be focused on a definite objective of which he is fully conscious, or his energy may be focused on a vague goal of which he is not fully conscious. The strength of the character's motivation. The Prince of Denmark, the title character, and the protagonist. About thirty years old at the start of the play, Hamlet is the son of Queen Gertrude and the late King Hamlet, and the nephew of the present king, Claudius. Hamlet is melancholy, bitter, and cynical, full of hatred for his uncle’s scheming and disgust for his mother’s sexuality.

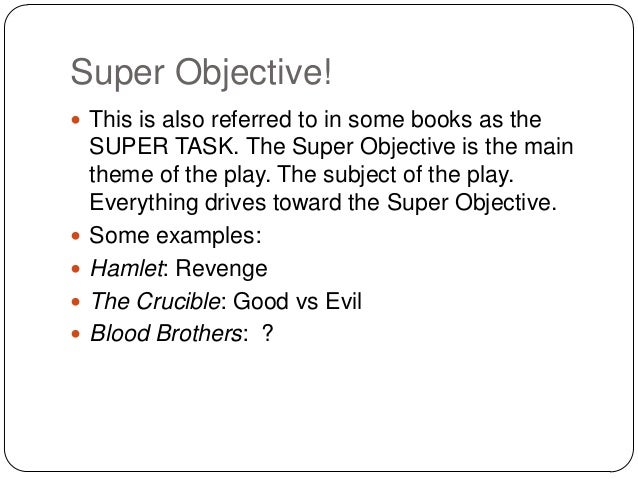

- Super Objective Theatre

- Super Objective Definition Acting

- Each Character's Super Objective In Hamlet Analysis

- Each Character's Super Objective In Hamlet Movie

Hamlet’s confusing and truncated relationship with Ophelia and his inadvertent murder of Polonius have made the two young men virtual enemies. In the end, Laertes accomplishes his main objective.

In literary criticism, an objective correlative is a group of things or events which systematically represent emotions.

Theory[edit]

The theory of the objective correlative as it relates to literature was largely developed through the writings of the poet and literary critic T.S. Eliot, who is associated with the literary group called the New Critics. Helping define the objective correlative, Eliot's essay 'Hamlet and His Problems',[1] republished in his book The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism discusses his view of Shakespeare's incomplete development of Hamlet's emotions in the play Hamlet. Eliot uses Lady Macbeth's state of mind as an example of the successful objective correlative: 'The artistic 'inevitability' lies in this complete adequacy of the external to the emotion….', as a contrast to Hamlet. According to Eliot, the feelings of Hamlet are not sufficiently supported by the story and the other characters surrounding him. The objective correlative's purpose is to express the character's emotions by showing rather than describing feelings as discussed earlier by Plato and referred to by Peter Barry in his book Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory as '...perhaps little more than the ancient distinction (first made by Plato) between mimesis and diegesis….' (28). According to Formalist critics, this action of creating an emotion through external factors and evidence linked together and thus forming an objective correlative should produce an author's detachment from the depicted character and unite the emotion of the literary work.

The 'occasion' of Eugenio Montale is a further form of correlative.The works of Eliot were translated into Italian by Montale, who earned the 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature.[2]

Origin of terminology[edit]

The term was first coined by the American painter and poet Washington Allston (1779-1843), and was introduced by T.S. Eliot, rather casually, into his essay 'Hamlet and His Problems' (1919); its subsequent vogue in literary criticism, Eliot said, astonished him.In 'Hamlet and His Problems',[3] Eliot used the term exclusively to refer to his claimed artistic mechanism whereby emotion is evoked in the audience:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an 'objective correlative'; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.

It seems to be in deference to this principle that Eliot famously described the play Hamlet as 'most certainly an artistic failure': Eliot felt that Hamlet's strong emotions 'exceeded the facts' of the play, which is to say they were not supported by an 'objective correlative'. He acknowledged that such a circumstance is 'something which every person of sensibility has known'; but felt that in trying to represent it dramatically, 'Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him'.

Criticisms[edit]

One possible criticism of Eliot's theory includes his assumption that an author's intentions concerning expression will be understood in one way only. This point is stated by Balachandra Rajan as quoted in David A. Goldfarb's 'New Reference Works in Literary Theory'[4] with these words: 'Eliot argues that there is a verbal formula for any given state of emotion which, when found and used, will evoke that state and no other.'

Examples[edit]

A famous haiku by Yosa Buson entitled, The Piercing Chill I Feel illustrates the use of objective correlative within poetry:[5]

The piercing chill I feel:

my dead wife's comb, in our bedroom,

under my heel...

In the Clint Eastwood movie Jersey Boys, songwriter Bob Gaudio of The 4 Seasons is asked who the girl is in his song Cry For Me. He makes reference to T.S. Eliot's topic, 'the Objective Correlative', as the subject being every girl, or any girl. In adherence to this reference, the author allows himself the literary license to step outside the scope of his personal experience, and to conjecture about the emotions and responses inherent with the situation, and utilize the third party perspective in the first party presentation.[6]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^Hamlet and His Problems

- ^G. Marrone; P. Puppa; L. Somigli (2007). Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies: A-J. London, New York: Routledge. p. 47. ISBN9781579583903. Retrieved Oct 3, 2018.

- ^Eliot, T.S. ''Hamlet and His Problems.' The Sacred Wood'. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^'New Reference Works in Literary Theory'. www.echonyc.com. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^Objective Correlative, March 31, 2015, retrieved April 26, 2015

- ^Eastwood, Clint (Director) (June 20, 2014). Jersey Boys (Motion picture). United States: MK Films, Malpaso Productions.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)

Super Objective Theatre

References[edit]

- Barry, Peter: Beginning Theory. An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. 2nd ed. New York: Manchester University Press, 2002.

- Eliot, T. S. 'Hamlet and His Problems.' 5 April. 2007. http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw9.html.

- Goldfarb, David A. 'New Reference Works in Literary Theory.' Conference: a journal of philosophy and theory, 1995. 9 April 2007. http://www.echonyc.com/~goldfarb/encyc.htm.

- Heehler, Tom. The Well-Spoken Thesaurus: The Objective Correlative and Barbara Kingsolver. Sourcebooks, 2011.

- Vivas, Eliseo, The Objective Correlative of T. S. Eliot, reprinted in Critiques and Essays in Criticism, ed. Robert W. Stallman (1949).

- Witkoski, Michael. 'The bottle that isn't there and the duck that can't be heard: The 'subjective correlative' in commercial messages.' Studies in Media & Information Literacy Education. Vol. 3. Toronto: Toronto Press, 2003. 9 April 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20110927010329/http://www.utpjournals.com/simile/issue11/witkoskifulltext.html.

External links[edit]

Hamlet

The son of Old Hamlet and Gertrude, thus Prince of Denmark. The ghost of Old Hamlet charges him with the task of killing his uncle, Claudius, for killing him and usurping the throne of Denmark. Hamlet is a moody, theatrical, witty, brilliant young man, perpetually fascinated and tormented by doubts and introspection. It is famously difficult to pin down his true thoughts and feelings -- does he love Ophelia, and does he really intend to kill Claudius? In fact, it often seems as though Hamlet pursues lines of thought and emotion merely for their experimental value, testing this or that idea without any interest in applying his resolutions in the practical world. The variety of his moods, from manic to somber, seems to cover much of the range of human possibility.

Old Hamlet

The former King of Denmark. Old Hamlet appears as a ghost and exhorts his son to kill Claudius, whom he claims has killed him in order to secure the throne and the queen of Denmark. Hamlet fears (or at least says he fears) that the ghost is an imposter, an evil spirit sent to lure him to hell. Old Hamlet's ghost reappears in Act Three of the play when Hamlet goes too far in berating his mother. After this second appearance, we hear and see no more of him.

Claudius

Old Hamlet's brother, Hamlet's uncle, and Gertrude's newlywed husband. He murdered his brother in order to seize the throne and subsequently married Gertrude, his erstwhile sister-in-law. Claudius appears to be a rather dull man who is fond of the pleasures of the flesh, sex and drinking. Only as the play goes on do we become certain that he is indeed guilty of murder and usurpation. Claudius is the only character aside from Hamlet to have a soliloquy in the play. When he is convinced that Hamlet has found him out, Claudius eventually schemes to have his nephew-cum-son murdered.

Gertrude

Old Hamlet's widow and Claudius' wife. She seems unaware that Claudius killed her former husband. Gertrude loves Hamlet tremendously, while Hamlet has very mixed feelings about her for marrying the (in his eyes) inferior Claudius after her first husband's death. Hamlet attributes this need for a husband to her lustiness. Gertrude figures prominently in many of the major scenes in the play, including the killing of Polonius and the death of Ophelia.

Horatio

Hamlet's closest friend. They know each other from the University of Wittenberg, where they are both students. Horatio is presented as a studious, skeptical young man, perhaps more serious and less ingenious than Hamlet but more than capable of trading witticisms with his good friend. In a moving tribute just before the play-within-the-play begins, in Act Two scene two, Hamlet praises Horatio as his soul's choice and declares that he loves Horatio because he is 'not passion's slave' but is rather good-humored and philosophical through all of life's buffets. At the end of the play, Hamlet charges Horatio with the task of explaining the pile of bodies to the confused onlookers in court.

Polonius

The father of Ophelia and Laertes and the chief adviser to the throne of Denmark. Polonius is a windy, pedantic, interfering, suspicious, silly old man, a 'rash, intruding fool,' in Hamlet's phrase. Polonius is forever fomenting intrigue and hiding behind tapestries to spy. He hatches the theory that Ophelia caused Hamlet to go mad by rejecting him. Polonius' demise is fitting to his flaws. Hamlet accidentally kills the old man while he eavesdrops behind an arras in Gertrude's bedroom. Polonius' death causes his daughter to go mad.

Ophelia

The daughter of Polonius and sister of Laertes. Ophelia has received several tributes of love from Hamlet but rejects him after her father orders her to do so. In general, Ophelia is controlled by the men in her life, moved around like a pawn in their scheme to discover Hamlet's distemper. Moreover, Ophelia is regularly mocked by Hamlet and lectured by her father and brother about her sexuality. She goes mad after Hamlet murders Polonius. She later drowns.

Laertes

Polonius' son and Ophelia's brother. Laertes is an impetuous young man who lives primarily in Paris, France. We see him at the beginning of the play at the celebration of Claudius and Gertrude's wedding. He then returns to Paris, only to return in Act Four with an angry entourage after his father's death at Hamlet's hands. He and Claudius conspire to kill Hamlet in the course of a duel between Laertes and the prince.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

Friends of Hamlet's from the University of Wittenberg. Claudius invites them to court in order to spy on Hamlet. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are often treated as comic relief; they are sycophantic, vaguely absurd fellows. After Hamlet kills Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are assigned to accompany Hamlet to England. They carry a letter from Claudius asking the English king to kill Hamlet upon his arrival. Hamlet discovers this plot and alters the letter so that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are put to death instead. We learn that they have indeed been executed at the very close of the play.

Fortinbras

The Prince of Norway. In many ways his story is parallel to Hamlet's: he too has lost his father by violence (Old Hamlet killed Old Fortinbras in single combat); he too is impeded from ascending the throne by an interfering uncle. But despite their biographical similarities, Fortinbras and Hamlet are constitutional opposites. Where Hamlet is pensive and mercurial, Fortinbras is all action. He leads an army through Denmark in order to attack disputed territory in Poland. At the end of the play, and with Hamlet's dying assent, Fortinbras assumes the crown of Denmark.

Osric

The ludicrous, flowery, stupid courtier who invites Hamlet to fence with Laertes, then serves as referee during the contest.

The gravediggers

Two 'clowns' (roles played by comic actors), a principal gravedigger and his assistant. They figure only in one scene -- Act Five scene one -- yet never fail to make a big impression on readers and audience members. The primary gravedigger is a very witty man, macabre and intelligent, who is the only character in the play capable of trading barbs with Hamlet. They are the only speaking representatives of the lower classes in the play and their perspective is a remarkable contrast to that of the nobles.

The players

A group of (presumably English) actors who arrive in Denmark. Hamlet knows this company well and listens, enraptured, while the chief player recites a long speech about the death of Priam and the wrath of Hecuba. Hamlet uses the players to stage an adaptation of 'The Death of Gonzago' which he calls 'The Mousetrap' -- a play that reprises almost perfectly the account of Old Hamlet's death as told by the ghost -- in order to be sure of Claudius' guilt.

A Priest

Charged with performing the rites at Ophelia's funeral. Because of the doubtful circumstances of Ophelia's death, the priest refuses to do more than the bare minimum as she is interred.

Reynaldo

Polonius' servant, sent to check on Laertes in Paris. He receives absurdly detailed instructions in espionage from his master.

Super Objective Definition Acting

Bernardo

A soldier who is among the first to see the ghost of Old Hamlet.

Marcellus

A soldier who is among the first to see the ghost of Old Hamlet.

Francisco

A soldier.

Voltemand

A courtier.

Cornelius

A courtier.

Each Character's Super Objective In Hamlet Analysis

A Captain

A captain in Fortinbras' army who speaks briefly with Hamlet.

Ambassadors

Each Character's Super Objective In Hamlet Movie

Ambassadors from England who arrive at the play's close to announce that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead.